Over the last thirty years, public discussions and private initiatives have tried to address longstanding issues of white-Black and settler-Indigenous tensions in North America. These conversations have been driven by discourses of “reconciliation,” especially in religious circles. But this notion is a product of a settler sentimentality that presumes to resolve centuries of oppression with ritual apologies.

But settler colonialism “is a structure, not an event.”

As Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang put it; reconciliation requires systemic transformation, not rhetorical contrition.

Desires of a complicit group for reconciliation without cost or radical personal and political change are little more than another grand “move to innocence.”

It is hardly surprising, then, that the semantics (and politics) of reconciliation are increasingly rejected as disingenuous by both Indigenous and Black activists.

Christians are often responsible for injecting such “cheapening” notions of grace into conversations about historical violations. But we also have resources to correct this drift toward “instant” exoneration, especially at the scriptural roots of our tradition. The Apostle Paul, for example, argues in 2 Corinthians 5:16-6:10 that reconciliation is indeed our core vocation: “God has given us the ministry of reconciliation” (2 Cor 5:18). But his vocabulary was hardly sentimental; the semantic field of the verb ‘to reconcile’ (Greek katallassō), used only by Paul in the New Testament is economic, not expiatory. In Aristotle, it connotes an exchange of money to establish the equivalence of value (like “reconciling” a bank statement).

Here reconciliation is fundamentally the restoration of justice—but it is “the justice of God” (5:21), understood (in contrast to Roman iustitia) not as retribution but redistribution. In situations of disparity between groups, this specifically means restoring equity: as the Apostle Paul puts it later, “your present surplus should help their need . . . in order that there may be equality” (2 Cor 8:14). Not to embrace practices of restorative justice is to receive grace “in vain” (2 Cor 6:1), argues Paul, which is precisely what we white settlers do when we expect reconciliation without practices of equal justice—what Bonhoeffer famously called “cheap grace.”

The problem is that the culture of modern capitalism considers any form of serious wealth redistribution to be heretical. This is why the songlines of our scripture are crucial for reinvigorating political imagination.

To strengthen Paul’s “course-correction” regarding reconciliation, we offer a brief recontextualized reading of Mark’s infamous gospel story of Jesus and the rich man (Mk 10:17-31).

In the sweep of Mark’s narrative, the privileged cannot enter the Kingdom of God through “intellectual assent” (as with the scribe in 12:34), nor through “sympathy” (as with Josephus in 15:43), and certainly cannot inherit it, as the rich man would assume (10:17). Relinquishment and reparation are the only vaccine for the killing of the virus of entitlement. Mark’s archetypal tale speaks as a deeply unsettling allegory for those of us who are rich relative to the global distribution of wealth and power, and whose affluence has been built over centuries of settler genocidal policies toward Indigenous peoples and dispossession of their lands and resources. Let us re-narrate this story (with some poetic license) as an encounter between “Indigenous Jesus” and “powerful settler official.

It begins with the settler official’s desire (command, even) to be enlightened by a Native “shaman” (10:17). Recognizing the official’s religiously-cloaked entitlement, Jesus coolly rebuffs his attempt to ingratiate himself through idealizing Native spirituality (10:18), and sharply reminds him about basic treaty obligations—in which this official is supposed to be well-versed. Jesus underlines treaty abrogations of murder, theft, lying, and fraud (10:19). The settler, predictably, responds with a dramatic move to innocence (10:20).

Indigenous Jesus now practices decolonization as radical love, pressing the truth that liberation means repatriation (10:21). The official freezes, bound and blinded by his ideologies of ownership and control which define his management of vast properties that were once Native homelands. Then he withdraws, no longer so interested in “reconciliation” (10:22). This surely should resonate with us: we too are practiced at halting our inquiries and engagements shy of reparation. But Indigenous Jesus is not done.

He now turns to his motley crew of fellow Native resisters to decode the encounter as an object lesson. Settlers, he says, only ever negotiated treaties with our ancestors for that to which they already felt entitled. Through murder, theft, lying and fraud they commandeered most of our territories. So, he intones in a solemn refrain, no reconciliation without repatriation (10:23–25)!

It is now Jesus’ companions’ turn to retreat, convinced (by hard experience) that this is too much to demand from the settler state (10:26). It is as dissonant to our ears as it was to theirs, and it provokes the same kind of astonishment: we cannot imagine a world in which stolen land has been returned, resources redistributed, and crimes atoned for. To their skepticism, and to ours, Indigenous Jesus replies: I know it seems impossible to you, but for Creator all things are possible (10:27). Decolonization is ultimately a matter of theological and political imagination.

Do you mean, asks one dispirited follower, that we should return to our traditional ways, to which you called us at the beginning of our movement (10:28)? The Teacher demurs about whether they have yet grasped his vision. But in the same breath he reiterates that the Good Way will restore original abundance for all—if the ancient laws of sufficiency, egalitarianism, and mutual aid are practiced (10:29–30). They will oppose us at every turn, he adds, but know this: though we who were first on this land are now last, this too will be reversed (10:31).

Over two millennia this tale has rarely been received as good medicine by those of us who are inheritors of the rich man’s system. Nevertheless, it speaks clearly to a settler Christian discipleship of decolonization. Its concluding promise that the world will be turned “right-side up” is distressing only to those of us who live near the top of a toxic hierarchy. Thus Paul, one of Jesus’ first interpreters, understood discipleship as a vocation of redistributive justice. This Second Testament vision has eluded our settler faith and practice for too long. It is time to “get up” (Mk 10:21) onto this healing Way of shared abundance and become ambassadors of reconciliation as reparations.

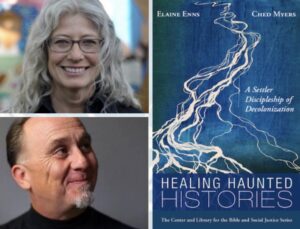

Elaine Enns has worked across the restorative justice field since 1989, from facilitating victim-offender dialogue in the Criminal Justice System to addressing historical violations and intergenerational trauma.

Ched Myers is an activist theologian and New Testament expositor working with peace and justice issues. He has published over a hundred articles and eight books.

Co-sponsored by the Center for Ecological Regeneration and the Stead Center for Ethics and Values in support of Garrett’s Indigenous Study Committee. View past webinars here.